Introducing the Cultural Booth of the Palestine Solidarity Forum: Two Years of Resistance, Two Years of Solidarity. This booth is filled with the life and art of Palestine, prepared directly by Palestinians in Korea.

Watch the richness of Palestinian life and art!

Table of Contents

- Keffiyeh

- Tatreez

The Palestinian Thobe: A Living Record of History and Identity - Artworks of Rena

- Dabkeh

- Fragmented Land, Enduring People

Palestinian Names: The Memory of the Land and the Struggle of Identity

Keffiyeh

The keffiyeh is a traditional West Asian headdress with origins that reach back to ancient Mesopotamia, where similar cloths were worn as symbols of honor and as practical garments to protect against the harsh elements. Over time, the keffiyeh became a fixture of everyday life among Bedouin tribes and farmers across the region, valued for its ability to shield against sun, sand, and cold. Different regions developed their own distinct patterns and styles, making the keffiyeh both a practical tool and a marker of cultural identity.

In the 20th century, the keffiyeh took on a new meaning as a symbol of Palestinian nationalism and resistance. During the 1936–39 Arab Revolt against the British, the black-and-white checkered keffiyeh gained prominence as a unifying garment for protestors, allowing them to blend in with the rural population. When the British authorities attempted to ban it, Palestinians adopted it even more widely as a collective act of defiance. During periods when Israel banned the Palestinian flag, the keffiyeh itself served as a de facto emblem of the Palestinian nation.

The black lines within the keffiyeh’s pattern also carry symbolic meaning. They are often interpreted as representing trade routes that once connected Palestine to the wider region, while the surrounding designs symbolize olive trees and fishing nets, images of sustenance and livelihood. Together, these motifs weave Palestinian history, geography, and daily life into the fabric of the garment, transforming it into more than clothing: it becomes a living archive of cultural memory.

Today, the keffiyeh is recognized globally as a symbol of Palestinian identity, resilience, and solidarity. For Palestinians, it represents pride in their culture, a connection to their homeland, and a spirit of strength in the face of oppression. Beyond Palestine, people around the world wear it as an emblem of solidarity with the Palestinian struggle.

The keffiyeh remains one of the most enduring and visible symbols of Palestinian resistance and belonging; an everyday garment elevated into a powerful political statement, carrying with it centuries of history, identity, and struggle.

Tatreez

The Palestinian Thobe: A Living Record of History and Identity

By Nareman (Palestinian, PhD Student)

The Palestinian thobe is not just a traditional garment, but a living document of Palestine’s history, cultural identity, and social fabric spanning thousands of years. If we look at the inscriptions discovered in Jericho, we find stunning geometric drawings dating back about 4,500 years, from the Canaanite era, most notably the eight-pointed star. This star was not merely decoration, but a way for women to express their daily lives, the condition of their village, the resources available to them, and the land they cultivated. From this, we understand that every stitch in the thobe carries a complete story about place and time.

For example, the Bethlehem thobe is distinguished by the eight-pointed star at the center of its embroidery. Contrary to the belief that it is a universal symbol, it was a way for women to record the history and customs of the city, telling us about its economic life, agricultural activities, and the social status of its women. Although the motifs may resemble those of the ancient Canaanites, their meanings in the Palestinian thobe are different. They do not symbolize religious rituals or celestial bodies, but instead daily life and the local identity of each village.

The Palestinian stitches themselves resemble a coded language. The falahi (peasant) stitch, which appears frequently on most thobes, reflects the woman’s connection to the land and agriculture. The “ant stitch” symbolized diligence and precision and was often used by women working in the fields. The “sickle stitch” referred to the harvest season and fertility, while the “spike and wheat stitch” reflected abundance and stability. The Bedouin “twist stitch” expressed strength and resilience among desert women. Each stitch told anyone who looked at it about the woman’s condition, her role in society, and her village’s economic standing.

The thobes also differed clearly from one village to another. The Jaffa thobe was characterized by warm colors and orange and lemon motifs, reflecting the city’s agricultural and commercial activity as well as the wealth of its people. The Bethlehem thobe was known for its precise embroidery, the eight-pointed star, and its purple and pink colors that symbolized the city’s religious and historical status. In Hebron, we find vine motifs and dark decorations that reflect the fertility of the land and its advanced handicrafts. Jerusalem’s decorations were inspired by domes and religious architecture, and its dark colors reflected the religious and social status of its people. In Gaza, the thobes were decorated with large flowers in bright colors, while in Beersheba the orange desert tones and Bedouin patterns reflected desert life and resistance to harsh nature.

A woman’s social status was clearly reflected in her thobe. A bride wore a white thobe adorned with delicate, colorful embroidery that expressed joy and new beginnings. A newly married woman’s thobe reflected marital stability, while a widow wore a black thobe with limited embroidery, sometimes with blue additions to express mourning. Women working the land wore practical dark thobes, often decorated with motifs symbolizing their connection to the soil. Older women’s garments were rich with patterns and colors, reflecting wisdom and family experience.

Over time, the Palestinian thobe became a symbol of resistance and resilience. After the Nakba of 1948, embroidered thobes became a source of livelihood, as women sold them to provide daily sustenance for their families. In the 1980s, during the First Intifada, the thobe turned into a national banner when the occupation banned the raising of the Palestinian flag. Women embroidered the flag’s colors and historical and political symbols onto their thobes, turning them into tools of protest and expressions of Palestinian identity, earning the name “Intifada Thobe.”

Despite Israeli attempts to steal this heritage—displaying Palestinian thobes in museums under misleading labels or using them in official fashion shows—Palestinians have held firmly to their ancient garments and embroidery art, passing it down from generation to generation as a living document that cannot be falsified. Global recognition came in 2021 when UNESCO inscribed Palestinian embroidery on the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage, making the thobe a global symbol of Palestinian identity and resilience through the ages.

In short, every stitch and motif in the Palestinian thobe is not just decoration, but a story of a village, of women’s lives, of economy, of nature, and of endurance. Through these thobes, we can read the history of Palestine, its customs, its culture, and even the standard of living in each community. The Palestinian thobe thus becomes more than a garment—it is an open book narrating the history of an entire people. In this way, Palestinian women, their creativity, and perhaps we can also say their sense of beauty, became one of the most important tools of recording Palestine’s history. They are among the foremost historians of Palestine.

Artworks of Rena

By Rena (Palestinian in S.Korea, Painting Master’s Student)

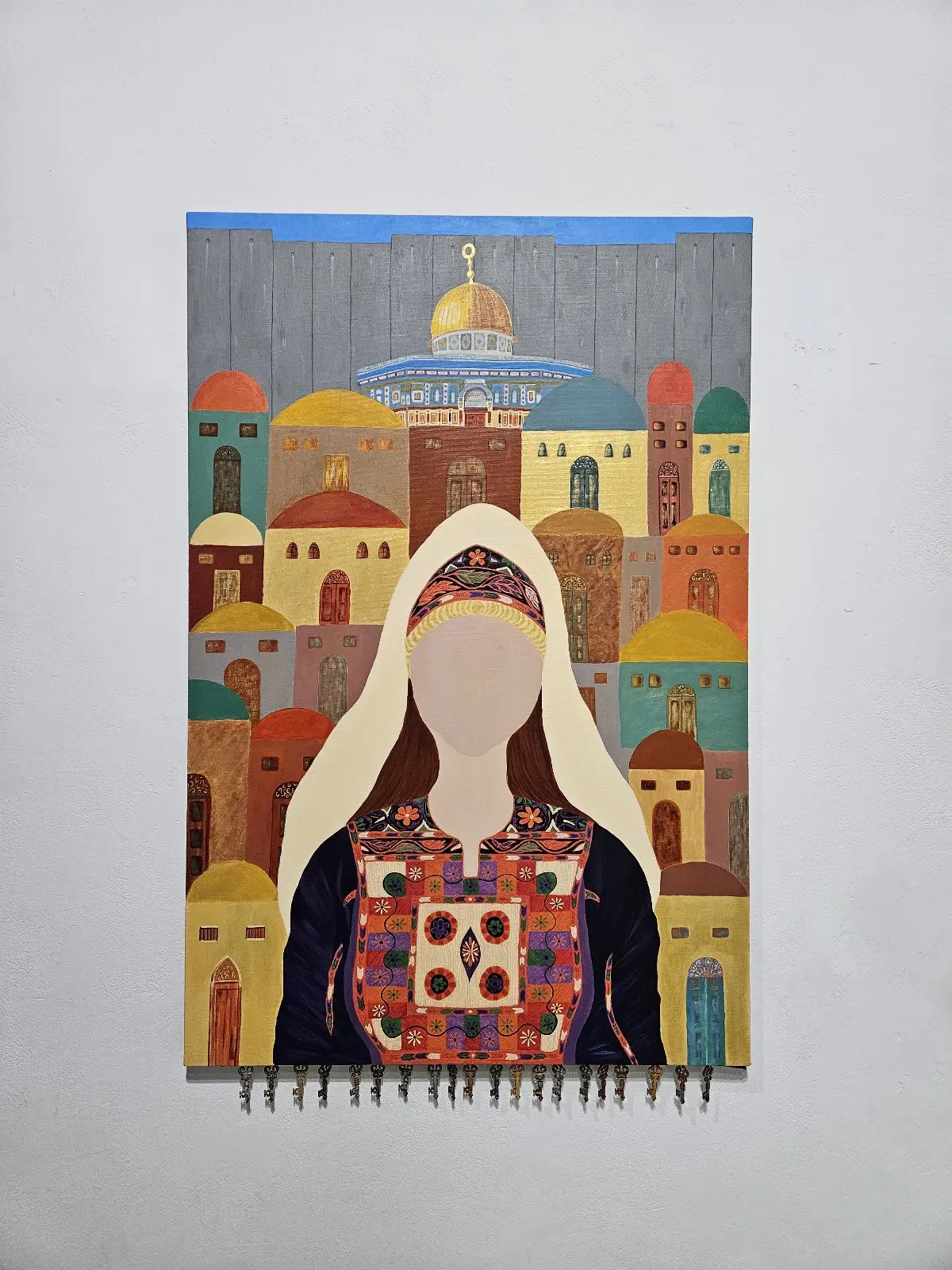

The Lady of the Land

This painting portrays a faceless woman cloaked in the richly embroidered Bethlehem thobe. Her absence of features is intentional—she is not one woman, but all women. She embodies mothers, daughters, and grandmothers whose stories weave together the collective memory of Palestine.

The thobe itself becomes her voice: every stitch is an archive, preserving the landscapes, flowers, and patterns of Palestine, passed down through generations as acts of both beauty and resistance. Behind her stand the old Palestinian houses—homes from which families were forced to flee in 1948. At the bottom of the canvas, keys hang as silent witnesses, symbols of loss but also of return. Many Palestinian women still carry these keys, holding onto the promise that one day the doors will open again.

The Lady of the Land is both a lament and a celebration. It mourns absence and displacement, yet it also honors resilience. She stands as a reminder that women’s roles in resistance—though often unrecognized—remain vital, enduring, and deeply rooted in heritage.

Threads of Legacy

In Threads of Legacy, the canvas centers on an elder woman’s hands—aged, steady, and absorbed in the act of embroidery. Clothed in a traditional thobe, only her chest, hands, and the fabric she works on are shown, highlighting action over identity. A single green thread flows from her hands and extends beyond the painting, connecting to an installation where two hands hold a piece of embroidered fabric—stitched directly with needle and thread.

This thread is more than fiber; it is a lifeline across generations. It binds the wisdom of the past to the hope of the future, showing how heritage and resilience are transmitted from one woman to another. Palestinian embroidery has always been more than decoration. It is a record, a map of identity, documenting the unique flowers, animals, and patterns of each village and city.

Through this piece, I invite viewers to see resistance not only as an act of defiance, but also as inheritance. It is something nurtured, passed down, and carried proudly—an enduring spirit that continues to bloom, stitch by stitch, across our people and our land.

Dabke

A Study by Sharaf Darzaid

Popular Art Center – Al-Bireh, Palestine – 2013

Introduction

Palestinian dabkeh is a folkloric dance that emerged from within the community and remains deeply tied to collective expression. According to researcher Abdel Aziz Abu Hudba, dabkeh is a musical-lyrical practice associated with instrumental accompaniment and collective performance, defined as a unisonal, rhythmic movement performed by individuals that expresses something shared by the group, reflecting the broader social and environmental atmosphere.

It is difficult to define Palestinian dabkeh apart from other Arab folkloric traditions, as it is widespread in Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Yet, under the particular political and historical conditions of Palestine, it acquired unique characteristics, becoming infused with vitality and emotion, and expressing pride, dignity, resistance, and steadfastness. Dabkeh thus became a symbol of Palestinian identity and resilience, without dispute.

Origins and Evolution

Some accounts trace dabkeh back to village life, when people built their homes from clay. After construction, men would stomp the soil with their feet to compact it while chanting folk songs. These rhythmic movements and songs gave birth to dabkeh, a dance born of community and cooperation, belonging not to an individual but to the collective.

Over time, dabkeh developed into an essential ritual of Palestinian weddings, performed as a central and unifying practice. Later, it expanded onto theater stages and festivals, inspiring folkloric troupes to create choreographed performances derived from traditional forms. Among these are styles known as al-Tayyara, al-Khaliliyya, al-Jawfiyya, al-Mahdalawi, al-Shamaliyya, al-Darzi, al-Sharawiyya, and al-Jafra, among others.

Structure of Performance

Dabkeh is performed in a circular or semi-circular formation. The dancers, men or women, stand side by side, their arms interlocked or resting on one another’s shoulders, moving in synchronized steps. A leader, called the lawwih, stands at the end or in front of the line. He directs the group, demonstrating impressive steps, waving a handkerchief or stick, and calling out names of dance steps.

The lawwih is marked by physical agility, charisma, and improvisational talent. He energizes the dancers and the audience, adds variations, and corrects mistakes when necessary. His role is crucial in maintaining rhythm, organization, and enthusiasm.

Common terminology used by the lawwih includes commands such as “pull,” “push,” “close the circle,” “open,” “shabik” (interlock hands), and “mahh” (press together without allowing newcomers). These words coordinate the dancers, ensuring unity and flow.

Wedding Rituals

Weddings preserve traditional dabkeh rituals. Evening celebrations often begin with sahja (collective clapping and chanting), followed by hirja (men’s dance) and women’s group dances. Women may perform without instruments, relying on chanted verses, standing in lines or circles, and moving in synchronization.

Dabkeh performances differ by region. In Jerusalem, for instance, a dance may be called harqi, in northern Palestine it may be known as wahda w-nusf (“one and a half”), while in central Palestine it is sometimes referred to as mazlaj. These regional names reflect local variations of step, rhythm, and expression.

Types of Dabkeh

- Al-Sahja: Men form two opposing lines or a circle, clapping and chanting in call-and-response style. It emphasizes rhythm and poetic exchange.

- Al-Ghuraybah: Dancers interlock hands in two rows, moving in coordinated steps. It is often performed in festive gatherings, highlighting unity and shared effort.

- Al-’Ataba and Al-Dal’ona: Performed with poetic verses that may carry messages of love, struggle, pride, or resistance. The poetic improviser (zajjal) leads with verses, and the group responds.

- Al-Samer: A form of Bedouin performance combining poetry and dance, where one group recites or boasts and the other responds, sometimes with satire or prideful counter-verse. This is considered one of the most authentic expressions of Arab oral tradition.

Each style of dabkeh is linked to specific occasions, rhythms, and symbolic meanings, but all reflect communal values and heritage.

Dabkeh as Cultural Resistance

Palestinian dabkeh goes beyond entertainment; it is a form of resistance. It preserves cultural identity in the face of occupation and attempts to erase or appropriate heritage. Documenting and performing dabkeh affirms Palestinian existence, history, and attachment to the land.

This art has become a cultural front line, countering Zionist claims and narratives by asserting the historical continuity of Palestinian presence. The heritage of dabkeh, with its rituals, costumes, music, and movements, is an essential component of Palestinian civilization and cultural identity.

Conclusion

Dabkeh is one of the most important Palestinian folkloric traditions, combining music, poetry, rhythm, and movement into a communal performance. It carries with it values of cooperation, pride, resistance, and cultural endurance.

By practicing and documenting dabkeh—whether on the village ground, the wedding courtyard, the theater stage, or in film—Palestinians safeguard their heritage from distortion or theft. They reaffirm their existence, dignity, and right to cultural expression. Dabkeh is therefore not only a dance but also a declaration of identity, resilience, and belonging.

Fragmented Land, Enduring People

Palestinian Names: The Memory of the Land and the Struggle of Identity

Palestine is not merely a map on paper; it is a land that carries the history of an entire people in the names of its hills, valleys, rivers, villages, and cities. Every name tells a story and bears witness to the relationship between humans and the land for thousands of years. Names are not fleeting words but living markers of a life that continued since the Canaanites and Phoenicians, through the Arabs and Muslims who preserved these names and added new towns and neighborhoods, up to our present.

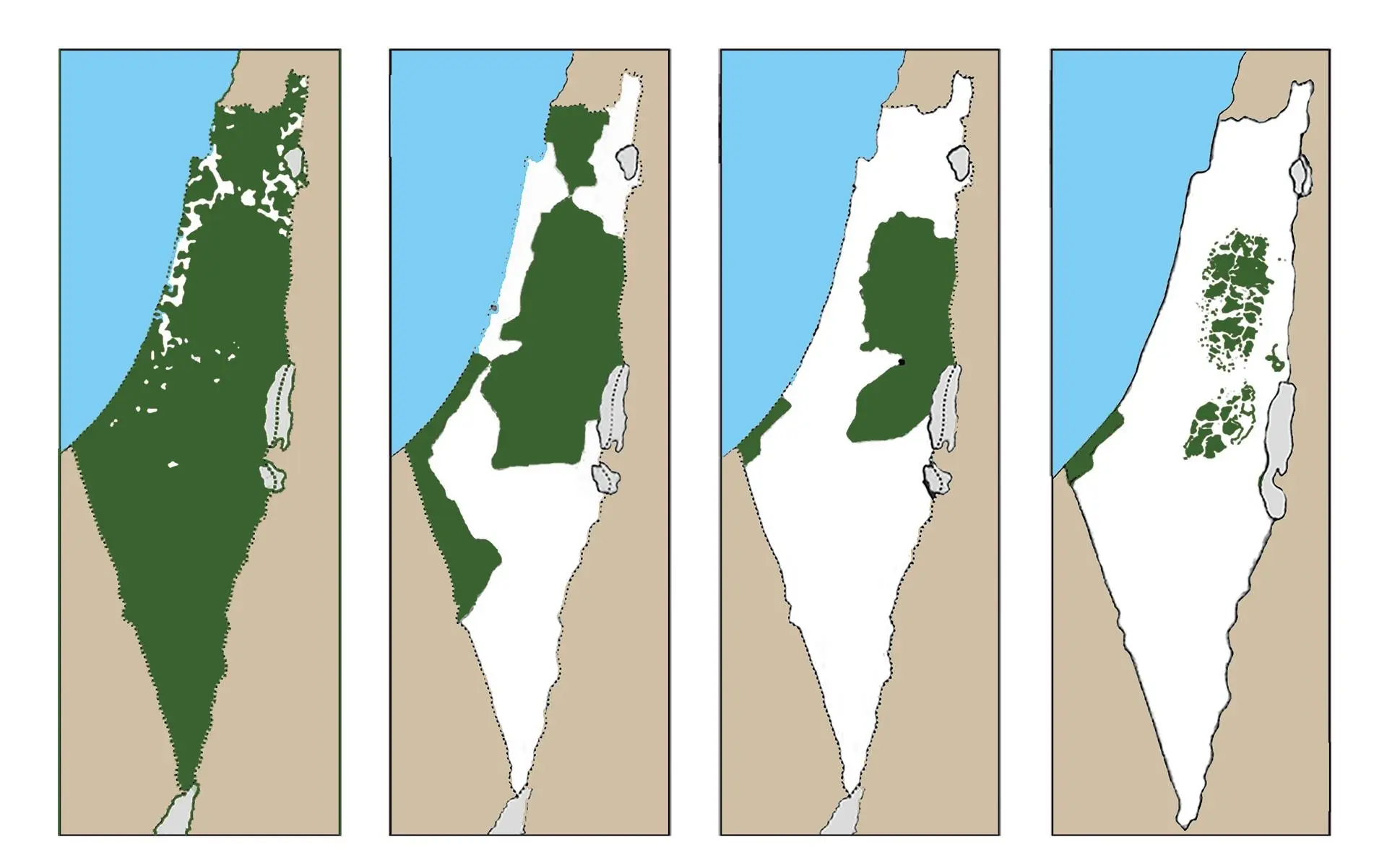

Loss of Land before 1948

The Palestinian tragedy did not begin suddenly with the Nakba in 1948; it was the result of a long sequence of policies. With the British Mandate, plans to partition the land began, and in 1947 the Partition Resolution was issued which granted Jews more than half of Palestine despite them being a minority. The goal was to pave the way for establishing a Zionist state and to guarantee the occupier’s control over the most important cities and ports such as Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Haifa.

After that came the Nakba: more than 750,000 Palestinians were displaced, over 500 villages were destroyed, and Palestinian lands were confiscated under the Absentees’ Property Law, which considered refugees “absent” and gave Israel the right to seize their properties. This law was a major step in erasing the Palestinian presence and imposing a new narrative on the land! The question remains — is it conceivable? Where did UN Resolution 194 go and our right of return?

The Oslo Accords and Their Results

The Palestinians signed the Oslo Accords in 1993 with the hope of returning to their independent state on the 1967 borders. Most Palestinians believed it was the beginning of reclaiming all the land, although I personally do not agree with it — but my mother is one of those who at the time welcomed it and is still somewhat in favor. She said, “You don’t know how we used to live before; now at least I have a document that says I am Palestinian — at least there is a paper that says I am Palestinian and not Arab!” Just as we were before the Palestinian Authority took over, and although I support the idea of having an identity, the question remains: is a conditional identity truly an identity? It was supposed that settlements would be gradually removed and roads would be opened freely to Palestinians, but reality went the other way. Instead of being removed, settlements multiplied, and the West Bank became divided into areas “A,” “B,” and “C,” beset by military checkpoints and a network of settler-only roads which Palestinians are not allowed to use. Lands that were supposed to be the borders of a Palestinian state became fragmented and isolated. For this reason, many young Palestinians now regard talk of a two-state solution as mere shirking of responsibility — on the ground things are different.

The Separation Wall: A Wound in the Body of the Land Trying Alone to Bury the Sunlight

The separation wall, which began to be constructed at the start of the millennium, was not merely a security barrier but a colonial project that divides the land and isolates villages from their agricultural lands. Thousands of dunams were confiscated, families became besieged, students need military permits to reach their schools, and farmers need permits to access their olive groves.

There was an international reaction: in 2004 the International Court of Justice issued an advisory opinion declaring the wall illegal and calling for its removal and compensation for affected Palestinians, but the wall remained standing as a symbol of the daily apartheid the Palestinian lives. For this reason it became a target for Palestinian youth to destroy; in every clash the youths burn and puncture the wall, certain that one day we will uproot it.

Settlements and the Forbidden Roads

Alongside the wall, highways were cut for the settlers occupying the land that run through the heart of the West Bank — roads Palestinians are not permitted to use!! These roads were not merely infrastructure but a calculated policy to separate the settlements from Palestinian villages and link them to Israel, turning Palestinian land into besieged islands. New settlements were built on the lands of Palestinian villages and destroyed parts of heritage and identity, becoming an essential part of the Judaization project. Unfortunately these roads continue to be carved without deterrent, and I wonder how the international community condemned the apartheid system in South Africa but is fine with Palestine.

Changing Palestinian Names: The Real Reasons

More than 80,000 Palestinian and Arab names have been changed since the beginning of the twentieth century, covering cities, villages, streets, and even religious sites. Jerusalem became “Yerushalayim,” Al Khalil “Hevron,” Nazareth “Natzrat,” Safed “Tzfat,” Lydd “Lod,” and Jaffa became part of “Tel Aviv–Jaffa.”

The real reasons for changing names are not superficial but were:

- Religious and Torahic legitimacy: linking Palestinian villages to names mentioned in the Torah to prove a “historical right” for Jews in the land, such as Baysan to “Beit She’an,” and Lydd to “Lod.”

- A new nationalist narrative: Israel wanted to present itself as an ancient state rooted in history, so a linguistic map was created to reflect this narrative and integrate the land into a Jewish national storyline.

- Erasing Palestinian identity: erasing the Palestinian name reduces the ability of future generations to recognize their cultural and social history.

- Scientific and political reasons: Zionist linguistic and geographic committees worked to systematically transform names to appear “scientific,” giving the project an official, documented character.

Canaanite, Arab, and Islamic Roots

Palestinian names were not created yesterday. Most date back to the Canaanites and Phoenicians:

Jaffa: “the beautiful,” a trading port for thousands of years.

Acre (Akka): from the root “akk,” meaning hot sand, a defensive and commercial center.

Gaza: strength and resilience, having withstood invaders through history.

Jerusalem: the Canaanite “Urushalim,” the city of peace.

Even when the Arabs and Muslims entered Palestine they did not erase these names; they preserved them and added new towns and neighborhoods linked to the natural landscape and daily life, such as Rama, Al-Bireh, Jabal Mukabbir, Ras Khalid.

Palestinian Resilience and Popular Memory

Despite Hebrew maps, the wall, and the settlements, Palestinian names remained alive in the people’s memory. Grandfathers and grandmothers tell their children the names of the old villages: “Safed,” “Jaffa,” “Beit Dajan,” “Al-Majdal,” “Al-Tantura.” These names became a symbol of cultural resistance because they carry a truth that cannot be erased.

Even the Palestinian thobe (traditional dress) reflects this memory: the embroidery was not merely ornament but a way to preserve the names of villages and historical symbols, like the Bethlehem star, which speaks of heritage, religion, and history.

In the End

Palestine is not just a political issue but a matter of memory and identity. Changing names, the wall, settlements, forbidden roads, and the Absentees’ Property Law are all tools attempting to erase history. Yet despite that, the Palestinian continues to utter the names of his old village, preserves the heritage orally and culturally, and resists attempts to erase his identity. Every hill, valley, and city carries a living memory proving that the land belongs to its people and that Palestine will remain alive in the memory of its children no matter how much new maps try to erase it. Even if our grandparents die, the memory of my village in my memory will remain engraved because of my ancestors, and I will pass it to my children and then to my grandchildren.